February

03

February

03

Gaye’s Purpose

Following Turkey’s elections, President Erdoğan empowered well-connected financial experts to return Turkey to economic orthodoxy. But is “orthodoxy” the solution to Turkey’s problems?

Since their victories in the May 2023 elections, Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his governing Justice and Development Party (AKP) have been signaling Turkey’s return to economic “orthodoxy.” Among the strongest of these signals was the appointment of Hafize Gaye Erkan as president of Turkey’s Central Bank. With credentials including a PhD from Yale and years at Goldman Sachs, it was understood that she would raise interest rates to combat inflation. Moreover, she would allow the currency to depreciate rather than spending large sums of foreign exchange to buy up lira, thereby artificially strengthening its value. Her appointment, along with that of “highly respected” Finance and Treasury Minister Mehmet Şimşek, were presented as positive developments in western media.

Now Erkan is out, replaced by one her vice-presidents, Fatih Karahan. The past two months were a test for her (and, by implication, the government’s commitment to its policies). In an interview with one of Turkey’s main newspapers, Erkan—well-paid and already wealthy from her time in the US—complained of the high cost of living in Turkey, the difficulty she had finding a house, and her decision to live with her parents. Opposition media criticized her for trying to portray herself as just “one of the people” and began focusing on the luxurious Ankara apartment the Bank was subsidizing. Problems for her increased in January, when it was reported that she had given her father an office in the Bank and that he was having staff fired. A day later came rumors that she had been in the US since New Year’s, with the implication that she might not be returning for long, if at all. President Erdoğan appeared to stop such talk by dismissing such “incomprehensible gossip.”

Erkan’s replacement, Karahan, has a biography that sends many of the same signals as hers did: degrees from Boğaziçi and the ivy league University of Pennsylvania; a decade of experience at the New York Federal Reserve; teaching positions at Columbia and NYU; and a brief stint as Amazon’s “principal” economist. An important question, however, is whether such orthodoxy is sufficient to solve Turkey’s economic troubles.

A look at Erkan’s career provides a reminder that what pleases Wall Street carries its own risks.

***

Just a month before Erkan was announced as Turkey’s new Central Bank president, First Republican Bank, the American institution at which she had made a name for herself, was seized by the US government and sold off to avoid a potential crisis. Erkan was not implicated in the debacle. She had left the bank a year earlier with a $10 million severance deal. Those former colleagues who had outlasted her in boardroom struggles were left to oversee the collapse.

Erkan joined First Republic in 2014. She was already highly-regarded. She had graduated from Turkey’s prestigious Boğaziçi University at the top of her class—in fact, with the highest grades in a decade—and gone on to Princeton, where she finished two years of doctoral course-work in just a year. By the time she earned her PhD, she had already been hired by Goldman Sachs, where she rose to the position of Director and Head of Financial Institutions Group Strategies, advising clients like First Republic on managing risk and dealing with government-mandated stress tests. Following the 2008 financial crisis, these tests were central to the Obama administration’s strategy for restoring confidence in the financial market. First Republic, however, avoided Federal Reserve stress tests by foregoing the holding-company corporate structure that would bring it under the relevant federal regulations. Though it was still overseen by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the bank spent heavily on lobbying in 2018, successfully encouraging the passage of laws that exempted it from higher levels of FDIC scrutiny.

In 2017, within three years of joining the bank, Erkan was named president. First Republic had assets of $76.5 billion at the time; these increased to $173 billion by the time she left in 2022. Erkan played a key role in this growth. The bank’s core strategy was to attract wealthy customers, offering them low-interest loans in return for large deposits. As president, Erkan encouraged the bank to market its services to wealthy millennials. For example, First Republic offered to refinance student loan debt over $40,000. The low-interest loans it offered were not a great deal for the bank in the short-term, but they established a connection with new customers, who were required to maintain checking balances over $3,500. (Given that average student loan debt was around $35,000, the bank was most likely targeting students who had gone to expensive schools, thereby earning degrees that would lead to high future earnings.) Erkan led the bank to buy Gradifi, a company that enables firms to repay their employees’ student loans.

First Republic was known for its attentive service to wealthy customers. Based in San Francisco, the bank was particularly focused on attracting clients from Silicon Valley including Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg. Erkan, however, remained on the east coast, helping expand the bank’s client base. As her own network grew, she was invited to join the board of the luxury brand Tiffany & Co. and Partnership for New York, an organization of the city’s business elite dedicated to urban improvement (albeit privately driven). In July 2021, Erkan was named co-CEO of First Republic. With founder and long-time CEO James Herbert taking medical leave, her accession to the bank’s leadership seemed imminent. Yet within six-months she resigned from the company. The reasons are unclear. A Financial Times story alluded vaguely to “toxic” interactions between her and other board members, but offered no additional details.

In some respects, her departure in January 2022 was well-timed. Since June 2020, the Federal Reserve had been maintaining interest rates at 0.08%, which benefited First Republic. The bank depended on wealthy people depositing their money despite the low interest it offered on deposits. In return, the bank offered them personalized service and large, low-interest loans. When interest rates were low everywhere, this was a good deal for the wealthy, since it gave them access to large loans that were not available at other banks. Starting in February 2022, however, the Federal Reserve began raising rates, reaching 4.57% in February 2023. Leaving large sums of money to earn minimal interest with First Republic began to lose its appeal. The only way to keep these wealthy clients was to offer better rates. But the bank’s main source of capital to pay higher rates came from the payments it received on mortgages and other large, long-term loans whose rates were low, set in the era of nearly zero-interest rates.

The contradictions of First Republic’s model led to a crisis in March 2022, following the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank. Like First Republic, they had catered to the wealthy. At SVB, around 90% of accounts were over the $250,000, which the FDIC guarantees to insure. Thanks to a rapid and vocal lobbying effort by politicians and tech industry investors, the US government stepped in and guaranteed accounts over the limit. But the collapses spooked wealthy depositors. At First Republic, around 68% of deposits were over the FDIC limit. Clients began withdrawing their deposits. Other banks deposited $30 billion with First Republic in March to restore confidence, but the bank’s announcement to shareholders on April 24 that assets had fallen to $104 billion (a 41% decline) caused its stocks to plummet. In less than a week, the bank was seized by the US government and sold to JP Morgan Chase, the largest US bank with assets of $3.9 trillion.

Erkan’s absence during this year of turmoil meant that she emerged with her reputation largely intact. At the same, she spent the year struggling to decide her next step. A month after leaving First Republic, she joined the board of the professional service firm Marsh McLennan. Soon after, she was named CEO of the real estate finance and investment firm Greystone. The latter position started in September 2023, but she left it just three months later. During the following months, in addition to her board positions, she helped raise money for victims of Turkey’s devastating earthquakes in February 2023.

***

It was in the aftermath of the 2023 earthquakes, with his political future appearing dire, that President Erdoğan began signaling a U-turn on economic policy. In March, he held a highly-publicized meeting with Mehmet Şimşek, a former minister of finance, who was symbolic of an earlier era of AKP economic governance. Şimşek was well-known to influential bankers in the US and UK. Prior to entering politics, he had worked for several years as an economist at the US embassy in Ankara, followed by a decade working for Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS), Deutsche Bank, and Merill Lynch.

Şimşek caught the attention of the AKP leadership in the mid-2000s. He was nominated for a post as vice-president of the Central Bank in 2006 along with a candidate for bank president, who was popular in Islamic banking circles. The nominations were rejected by secularist President Ahmet Necdet Sezer. But Şimşek won a seat in parliament in 2007 and immediately entered the cabinet as a state minister responsible for economic issues. From there, he became minister of finance, and then deputy prime minister.

While the Turkey of Şimşek’s first era (2007-2018) is now recalled as a time of sensible, orthodox economic management, it was not without its crises—or its critics.[1] More importantly, whether Şimşek advocated for them or not, this was a period in which many of Turkey’s current difficulties were coming into view. Faced with multiple shocks, the government tried to sustain economic growth through loose monetary policy. Electoral victories increasingly came to depend on repressing critics and maintaining the support of interest groups like small and medium businesses. In the latter case, the AKP sought to win support through ample credit. Banks were encouraged to issue loans. More money in the system weakened the lira. To prevent a dramatic fall in its value, policymakers periodically took measures that would become more reckless in later years: they used foreign exchange to buy up lira and prop up its value. Such actions kept the economy running hot but were risky. In its 2018 consultation report on Turkey, the IMF concluded “that the economy shows signs of overheating.” While ministers like Şimşek continued to defend the government publicly, journalists reported that, behind-the-scenes, their faction was still pushing for “reforms.”

Şimşek left just as Turkey’s new “presidential” system came into effect following the 2018 elections. During the campaign, President Erdoğan had emphasized his plans to exercise more control over economic policy and his dislike of fighting inflation with interest rate increases. After the election, institutions like the Central Bank were placed directly under executive control, and Erdoğan’s son-in-law Berat Albayrak was named minister of finance and treasury. The value of the lira fell on the announcement.

Though Albayrak was forced out in November 2020, the inflationary policies persisted. The Central Bank continued spending foreign exchange while implementing new, unsustainable policies to prop up the lira. Among the most risky was the creation of special savings accounts in which people could place lira for fixed periods of time with a guarantee that their money would maintain its original dollar value plus interest. When the accounts were opened in December 2021, the lira was worth $0.08. When they were finally closed to new deposits two years later, there was some TL2.65 trillion in the accounts ($92 billion) and the lira’s value had fallen to $0.03.

In the short-term, the government’s policies made sense. Low interest rates and ample credit to businesses helped Turkey maintain constant growth. In 2020, for example, as covid shut down the global economy, Turkey was one of the few countries whose GDP grew. But the hangover has been severe: annual inflation was already at 12.3% in 2020 and reached 72.5% by 2022. The cost of living has soared. The same concerns were present in the run up to the 2019 municipal elections. Then, the government opened temporary markets around major cities to sell subsidized groceries. Yet these actions did not prevent dramatic opposition victories in cities like Istanbul, Ankara, and Adana. Given that simply spending through the crisis was not enough in the last local elections, perhaps Erdoğan and his allies have opted to present themselves as sober economic managers in advance of the March 2024 elections.

***

The first meeting between Erdoğan and Şimşek in March 2023 was inconclusive. Afterwards, Şimşek tweeted that he was not ready to return to politics. By hedging in this way, he avoided nomination as an AKP candidate for parliament and retained the ability to bargain with Erdoğan about his ultimate degree of autonomy during the following months. His caution paid off: within days of Erdoğan’s second-round electoral victory, Şimşek was appointed as minister of treasury and finance with the expectation of broad authority. A day later, he was in New York to meet with Erkan and discuss her possible role as Central Bank president.

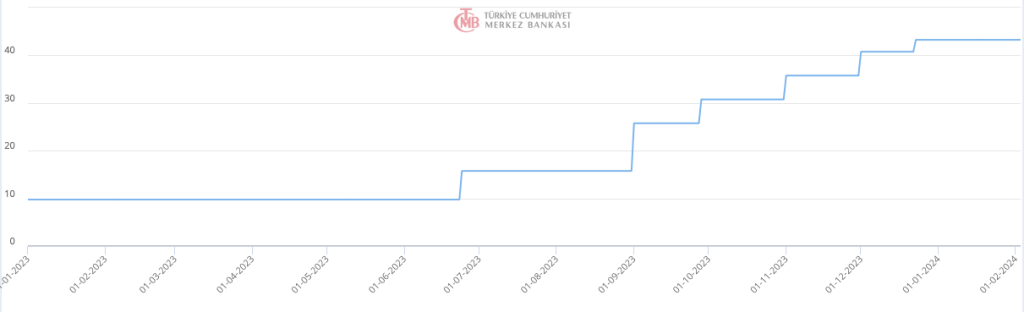

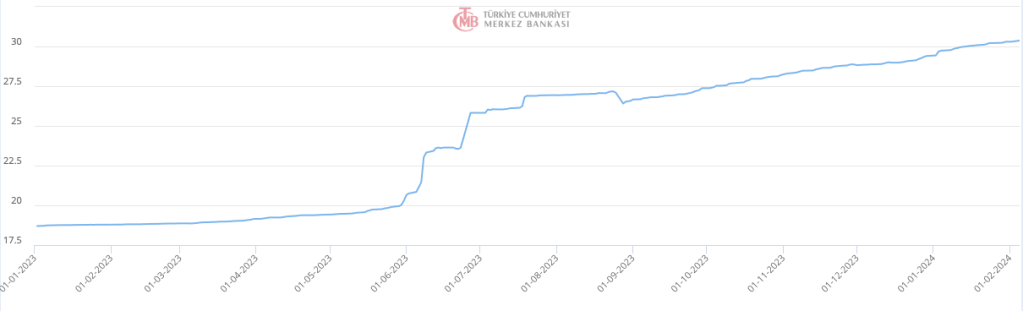

Şimşek and Erkan’s goal since June has been to restore Turkey’s creditability (in a very literal sense). During her seven months in office, Erkan raised interest rates from 8.5% to 45%. The special savings accounts are being phased out, and the percent of lira-denominated securities that banks must hold has been significantly reduced. The lira has been allowed to slide from around TL23.30 to the dollar to TL30.30, with predictions that it will reach TL40.64 by the end of 2024. Şimşek, meanwhile, has overseen substantial tax increases on petroleum and other consumer products in hope of deterring domestic consumption and reducing Turkey’s sizeable trade deficit.

The long-term goal is to reach single-digit inflation by the end of 2025. One difficulty in achieving these aims, however—and one that illustrates the contradictions of “orthodox” policymaking—is salary increases. The government has raised the minimum wage substantially in the past year. At the beginning of January 2023, the monthly minimum wage rose from TL5,500 ($294) to TL8,506 ($315). A month after the elections it was raised to TL11,402 ($422), and to TL17,002 ($578) at the beginning of 2024. The minimum wage is now higher in dollar terms than a decade ago (even factoring in the changing value of the dollar). Given the rising costs for basic goods, these increases are necessary, but they may be in tension with the goal of fighting inflation.

Together, Şimşek and Erkan traveled to countries like Saudi Arabia and Spain to give presentations and convince holders of capital that Turkey is again safe for investments. In New York, they gave presentations at JP Morgan. Şimşek has also traveled to the United Arab Emirates. Both Erkan and Şimşek represent the sort of “orthodox” economics popular with investors, but what counts as orthodoxy for the western financial networks in which they are embedded should raise eyebrows. The risky strategy of Erkan’s First Republic—wholesale dependence on the whims of the wealthiest 10% of Americans—was successful during her tenure but not sustainable. Similarly, it might be observed that Şimşek’s early private-sector experience was at UBS (a company with a history of illegal activity) and Deutsche Bank (which has spent the past decade accounting for its various misdeeds). His final employer before entering government, Merrill Lynch, was at the forefront of firms driving the economic crash of 2008. While not at the same level of leadership as Erkan, Şimşek also departed his firm just before it failed and was subsumed by a larger institution (in this case, Bank of America). In both his case and Erkan’s, the point is not to suggest guilt by association but rather that the “orthodox” system, which they represent, deserves close scrutiny.

In short, Şimşek and Erkan, were tasked with the job of making Turkey an inviting destination for international finance. But their own careers serve as reminders that international finance is not always a guest to be warmly welcomed.

[1] See, for example: Hasan Cömert and Mehmet Selman Çolak, “The Impacts of the Global Crisis on the Turkish Economy, and Policy Responses,” in The Global South after the Crisis: Growth, Inequality and Development in the Aftermath of the Great Recession, eds. Hasan Cömert and Rex McKenzie, 223-254 (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2016); Elif Karacimen, “Financialization in Turkey: The Case of Consumer Debt,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 16, vol. 2 (2014): 161-180; A. Erinç Yeldan and Burcu Ünüvar, “An Assessment of the Turkish Economy in the AKP Era,” Research and Policy on Turkey 1, no. 1 (2016): 11-28; Turkey’s New State in the Making:Transformations in Legality, Economy and Coercion, eds. Pınar Bedirhanoğlu, Çağlar Dölek, Funda Hülagü and Özlem Kaygusuz (Zed Books, 2020), especially chapters by Pınar Bedirhanoğlu (23-40), Ali Rıza Güngen (118-133), Melehat Kutun (134-150).