April

08

April

08

Local Ripples, National Wave

The startling success of opposition parties—the CHP chief among them—played out in provinces across Turkey. Consider several examples.

Compared to the results elsewhere, the local elections in Düzce went smoothly for the AKP. The province, located 200km east of İstanbul, is Turkey’s newest, only separated from neighboring Bolu in 1999 as part of an administrative reorganization follow a pair of destructive earthquakes.[1] Since evening on March 31, 2024, it has appeared on election maps as part of a small cluster of provinces in northwestern Turkey, defiantly supporting the Justice and Development Party (AKP) amid a sea of red, symbolizing opposition victories. Yet even this lonely victory reveals some of the larger trends of the election.

In 2019, with turnout high (around 89%), the AKP won Düzce’s central municipality mayoral race with 47.1% and the provincial assembly with 47.7%. In both cases, its nearest challengers were its own coalition partner, the far-right Nationalist Action Party (MHP), and the Good Party (İYİ), an MHP-breakaway party that was coordinating its candidates with the main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP). In the mayoral race, the MHP and İYİ won 21.8% and 28%, respectively. In the provincial assembly, the MHP did better (28.2%) and İYİ did worse (12.4%) with the some of that difference (8.1%) probably going to the CHP, which had not run a candidate against the İYİ mayoral nominee. Religious opposition in the province was represented by the Saadet (“Felicity”) Party, which criticizes the AKP’s Islamist bona-fides and won around 3,000 votes (1.2%) of the assembly vote.

In 2024, turnout fell. Whereas some 244,000 voters across the province cast ballots in 2019, in 2024, only around 203,000 did. In the voting for the province-wide assembly, 16,000 fewer people voted for the AKP, and its vote share fell to 39.4%. The MHP received 33,000 fewer votes, dropping by half to14.1%. But these nationalist votes did not go to İYİ, whose vote also collapsed (16,000 fewer votes, down to 5.5%). Some of these voters went to the CHP, which received 13,000 more votes than it had five years earlier.[2] In any event, most of the votes seem to have gone to the New Welfare Party (YRP).[3]

The YRP, led by Fatih Erbakan, is a relaunch of the Welfare Party led by his father, Necmettin, the founder of Turkey’s Islamist political movement. Though YRP had supported Erdoğan and the AKP as recently as last year’s presidential elections, it opted to contest the 2024 local elections with its own cadres after the AKP rebuffed the concessions it demanded for support (e.g., AKP support for YRP candidates in several major municipalities such as Bursa or Malatya).[4] In many races, YRP candidates took a sizeable portion of votes that might otherwise have gone to the AKP. Though there were only a few municipal mayoral races in which YRP’s presence clearly threw the election to the CHP, in many provincial assemblies (including İstanbul’s), it likely denied the AKP a majority.[5] [6]

In Düzce, YRP had its fourth-best performance nation-wide, either helped or hampered (it’s unclear to me!) by its choice of mayoral candidate: Davut Güloğlu, a popular singer from the early 2000s with a summer house on Düzce’s Lake Sapanca. His string of relationships, prosecutions and investigations for defaming (and abusing) women, apparent lack of knowledge about the province, and arguments with locals on the campaign trail either made him an odd standard-bearer for the party, or successfully conveyed a sense of masculine dominance that appeals to many voters.[7] (Given that he outperformed the party itself in the central municipality, it may be the latter.)

The conservative politics of Düzce—reflected in the combined 90% of the vote won by parties of the right in 2019—proved to be an insurmountable barrier for the CHP in the 2024 elections. But, in many provinces, these barriers collapsed. In provinces like Adıyaman or Afyonkarahisar, for example, which also have significant conservative blocs, the CHP candidates won the central municipal races with 49.7% and 50.7% of the vote, respectively. In these and other cases, the AKP was weakened on multiple fronts. As in Düzce, low turnout suggests many rank-and-file AKP supports simply didn’t show up to vote. Of those that did, the YRP pulled from the AKP’s religious-nationalist base, and the MHP—which, despite being the AKP’s ally at the national-level, often competes against it in local elections in conservative provinces—pulled from its ethic-nationalist base. Crucially, however, the CHP, on its own, was able to attract more voters than it ever has before, and its largest percent of the vote since 1977. The parties it relied on for victory in recent years did not significantly divide the vote: İYİ’s share of the vote collapsed and DEM, while winning some of its largest majorities yet in southeastern provinces, received few votes in western cities.

There is no single explanation for the election results, but rather a combination of national trends and local particularities. In the aftermath of the elections, there will certainly be an effort to pinpoint “the” explanation and fit these multiple factors into a tidy, useful narrative that can direct action going forward. But, at the local level, tidy narratives often break down.

The AKP share of the vote increased in mayoral races in only ten provinces. Moreover, in provincial assembly races, the AKP share increased in only three: Iğdır, 24.7% (+17.2), Aydın, 19.4% (+2.2), and Mersin, 9.1% (+0.6). As the chart shows, most of these gains were small, with the exception of Hakkari, where the DEM Party accuses the government of skewing the results by bussing in security officials stationed in the province to vote.The YRP and Şanlıurfa

While the YRP failed to win in Düzce, it still performed remarkably well. Nation-wide, the party won mayoral races in two provinces (Şanlıurfa and Yozgat) and came second in six others.[8]

In its two successful mayoral races, the YRP fielded popular candidates with long-standing ties to the provinces—and grievances against the AKP leadership. In Şanlıurfa, the candidate was Kasım Gülpınar, a long-time AKP member whose campaign emerged from his frustration at being passed over for the mayoral nomination. His decision to leave the AKP and join the YRP had far-reaching reverberations. Gülpınar is a leading member of the Kurdish Şeyhanlı tribe (aşiret), descended from a line of Nakşibendi shaykhs. His father, Cenap, entered national politics in the mid-1970s as a candidate for Necmettin Erbakan’s National Salvation Party (MSP)—a predecessor of both the AKP and the YRP. In 1987, he won a seat with the center-right Motherland Party (ANAP). He switched to the AKP for the 2002 elections and remained in parliament until 2011. He died a year later, but Kasım took on the role of parliamentarian, serving from 2011-2023.[9]

The influence of Gülpınar’s family extends to other tribes as well, and some reporting suggests that the AKP’s refusal to nominate him as mayor was part of an effort to rein him in. If so, it was a mistake. Gülpınar’s party switch led to mass resignations from local AKP branches in his home municipality of Siverek as well as lines of applicants at the YRP office in the central municipality of Eyyübiye. Even in the neighboring province of Adıyaman, where his tribe and allied tribes like the İzol are also well-established, there were switches to the YRP. Tribal politics was particularly apparent in Siverek, where the AKP backed a member of the powerful Bucak tribe as the municipal mayor after years of keeping the family at a distance. Gülpınar and the YRP backed a member of the İzol tribe. There had already been violence in recent years in Siverek over access to municipal contracts, and this election heightened tensions.[10]

Five years earlier, the AKP had won the metropolitan mayoral election with 60.8% of the vote, followed by the religious Saadet Party with 36.4%. No other major parties even contested the mayoral election—though, looking at the assembly vote, the HDP accounted for some 20% of that vote. In 2024, the HDP (now called “DEM”) ran a mayoral candidate and won 21.2%. The YRP and AKP split the religious vote 38.9% to 33.6% with Gülpınar emerging as the winner. In Siverek, however, the AKP candidate Ali Murat Bucak won by 64 votes (40.23% against 40.17% for Hasan İzol). Protests followed at the local courthouse, and Gülpınar appeared on the scene to calm his supporters. The following day, he spoke to reporters, promising—somewhat incongruously given the politics of the province—that the era of giving cushy jobs to friends and relatives (torpil) was at an end.[11]

In Yozgat, the other province in which the YRP won the central municipality’s mayoral race, it nominated Kazım Arslan. Like Gülpınar, Arslan’s campaign stemmed from being passed over by the AKP leadership. He had been active in Islamist politics in the province for decades. He had served as a representative in parliament during the Welfare Party’s mid-1990s heyday. After the party was banned and the Islamist movement fractured in the early 2000s, he had joined a faction, the Saadet Party. When his faction’s leader, Numan Kurtulmuş, split with Saadet and joined the AKP, Arslan followed. As an AKP member, he had served as mayor of Yozgat from 2014-2019. When the AKP’s provincial party president, Celal Köse, received the party’s nomination as mayor in 2019, however, Arslan launched an independent bid. In the 2019 election, Aslan came in second, only four points behind Köse. (As in many Anatolian provinces, the MHP also ran a candidate, which likely cut into Köse’s share of the vote.) In 2024, this match-up was repeated, but Köse received 6,000 fewer votes, coming in third, behind the MHP candidate. Aslan won the election with only around 500 more votes than he had won five years earlier.[12]

In other provinces where the YRP performed well, it fielded similarly strong candidates. In Kahramanmaraş, for example, it ran Muhammed Aydoğar, a young provincial party leader whose father, Mustafa, had been a local leader during the 1990s.[13] In Konya, it ran Mehmet Köseoğlu an experienced municipal official from a well-connected local family.[14]

During the elections, YRP hammered the AKP on its “debt-interest-price hike-tax” economic policies. It also pointed to the gap between President Erdoğan’s criticism of Israel’s ongoing slaughter of civilians in Gaza and Turkey’s continuing trade relations with Israel. Just days before the election, the YRP offered to pull out its İstanbul candidate if the government significantly raised the retirement age, cut ties with Israel, and closed a radar installation that allegedly provides information to Israel.[15] Coming just forty-eight hours before the polls opened, these demands were certainly just for show, but they highlighted the party’s campaign themes. At the same time, the party’s major victories demonstrated less its popularity than its ability to attract AKP dissidents and provide a home for their political networks. The victorious YRP candidates were not partisan ideologues, but rather canny politicians who sensed their local strength and resented the AKP national leadership for not acknowledging it. If the AKP can placate them in the years to come, it may be able to count on their support once again.

Though the YRP seldom won control of key mayorships or provincial assemblies, it won large shares of the vote in major central Anatolian provinces like Konya and Kayseri. In almost all cases, these results constitute huge shifts in support from ten months earlier, when the party hardly registered in most provinces.The DEM Party and Van

The fluidity within the Islamist political movement can also be seen in the Kurdish political movement.

Less than two days after the elections were over, protests erupted in Van. Despite winning the metropolitan municipality election with 55.5% of the vote, the DEM candidate, Abdullah Zeydan, had been denied his certification (mazbata). Instead, the local electoral commission certified the AKP candidate as winner (he had come in second with 27.1%). That Van was the first province to (yet again) have its popularly-elected mayor not allowed to govern was all the more significant because Van was the only province where a majority of every municipality voted for the DEM party candidate.

The rejection was in response to a last-minute complaint filed by the Justice Ministry on the last business day before the election. The Ministry argued that Zeydan’s past convictions should prevent him from serving. Zeydan was first elected to parliament in 2015 as a representative for Hakkari. He was arrested in 2016, along with several other representatives in 2016 and given a combined eight-year sentence for his involvement in protests, funerals, and other “terrorist organization propaganda.” He was released from jail in 2022 and was granted the right to stand as a candidate.[16] Given that the Justice Ministry had months to file its complaint, there is no justification for doing so at the last minute (or the court approving such a move). After several intense days of protests and appeals, the Supreme Elections Board (YSK) supported the appeal and acknowledged Zeydan’s right to receive his certification.

Zeydan is a member of the Piyaniş, a politically influential southeastern tribe based in the region around Hakkari. His father was mayor of Yüksekova municipality for years and served three terms in parliament as a representative for Hakkari, first as a member of the center-right True Path Party (DYP), later as a member of the AKP. From three marriages, his father had twenty-five children including Abdullah. Rüstem, one of Abdullah’s brothers is a doctor and founding member of the AKP. (He too represented Hakkari for a term.) He resigned from the AKP in 2019, when Abdullah was in prison. He joined the CHP in 2021 as then-leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu’s “chief health advisor.”[17] Among the other brothers, Teoman, a businessman, unsuccessfullysought a place on the AKP’s Van candidate list in 2015 and ran unsuccessfully as the AKP’s mayoral candidate for Yüksekova in 2019. İsmail Rüştü governed the Yüksekova town of Büyükçiftlik from 1994 until 2024, when the AKP did not renominate him and he was unable to win as a YRP candidate.[18]

These details about the extended Zeydan family illustrate the fluidity of political coalitions in Van, Hakkari, and other southeastern, predominantly-Kurdish provinces. On the one hand, even a candidate like Abullah Zeydan who is anathema to the AKP government is connected to politicians who are on friendly terms with the AKP, CHP, and YRP. This makes negotiation possible. On the other hand, Zeydan and other politicians have associations, however distant, with the PKK. (Yet another of his brothers, Yücel, was killed fighting for the PKK.) While these too can be useful in negotiations, they offer President Erdoğan’s government a ready-made justification for cracking down on politicians like Zeydan, who challenge centralized rule.[19]

In ten provinces, DEM controls both the central municipal mayoral post and the provincial assembly. In two more it controls the assembly but not the central municipal mayor post (i.e., Bitlis and Kars). In the races listed in this chart, the mayoral candidate's vote increased in all but five (i.e., Bingöl, Kars, Iğdır, Batman, and Hakkari). These declines were relatively small with the exception of Hakkari, where DEM accuses the government of "transferring" voters by bussing security forces stationed in the region into the polls.The İYİ Party and Nevşehir

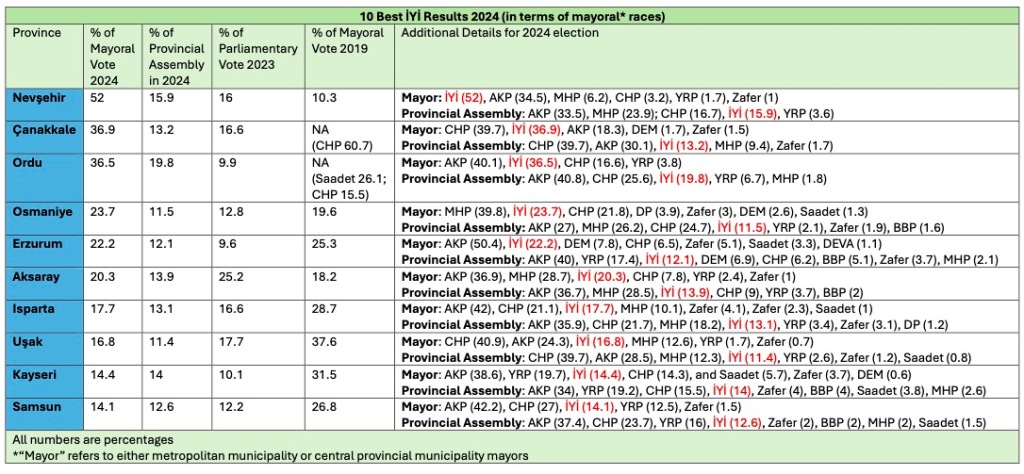

Whereas the 2024 elections allowed leaders of the Kurdish political movement an opportunity to, yet again, demonstrate their popular support, the elections were a disaster for İYİ. Since its establishment in 2017, the party had generally coordinated its campaigns with the CHP. These arrangements helped both parties: support from the right-wing İYİ protected CHP candidates like Ekrem İmamoğlu from charges of being tolerant of (or beholden to) Kurdish nationalists; at the same time, coordinated candidate lists shielded İYİ nominees from competition with CHP candidates in various races. Insulated from challenges, İYİ could win seats in parliament and make impressive showings in reliably pro-AKP provinces like Balıkesir (where it only narrowly lost in 2019).

By running on its own, however, İYİ revealed how limited its support was. In the İstanbul metropolitan mayoral race, the İYİ candidate won only 0.6% of the vote. In this particular race, of course, İYİ supporters’ decision to vote for the incumbent, İmamoğlu, might be understandable: only a year earlier, party leader Meral Akşener had been telling them that he was so qualified as to be president. But voters’ preference for the CHP over İYİ was clear in all İstanbul mayoral races. İYİ’s best performance in İstanbul was 3.5% in Arnavutköy, and in only four of the thirty-nine İstanbul races it contested did İYİ do better than the nativist Zafer Party, formed by a disgruntled founder of İYİ.[20]

Somewhat ironically, the 2024 elections were also the first occasion that İYİ won a major election, taking control of Nevşehir province’s central municipality (population 160,000). İYİ won 52% of the vote, leaving the AKP in the dust with 34%. Yet even this victory underscores the AKP collapse more than any İYİ success: the winning candidate, Rasim Arı, had also won in 2019—but as an AKP candidate. His switch to İYİ was due to a falling out with the AKP. In late 2020, the municipality had been investigated for “bribery and corruption.” The following month, unidentified attackers fired on Arı’s car. He resigned from the party a few weeks later citing “health” reasons. The provincial assembly elected Mehmet Savran, an AKP member, as his replacement. Eventually Arı began talking publicly (albeit vaguely) about the threats he and his supporters had faced. Opposition media reported that he had been forced out of office by the AKP, which was angry at him for not slowing the corruption investigation. He joined the İYİ in 2023 and launched a successful campaign against Savran, now the incumbent.[21]

Aside from its Nevşehir victory, İYİ came second in four major mayoral races: Çanakkale, Ordu, Osmaniye, and Erzurum. In many of these cases it nominated well-established local candidates. Its Ordu candidate, Enver Yılmaz, had been mayor from 2014-2018 as a member of the AKP, but resigned in 2018 after a squabble with the Vice President of the AKP, Numan Kurtulmus.[22] In Osmaniye, a MHP stronghold, its candidate Alpaslan Koca had been the MHP mayor of the municipality of Hasanbeyli from 2014 to 2019 and was a familiar actor in the province’s contentious right-wing politics. During his term, Koca was the target of two armed assaults—oneat wedding by a disgruntled former city employee, another in a hospital cafeteria, when a fight began between his son’s friends and another group. In 2019, the MHP nominated the incumbent, Kadir Kara, for a third term as its candidate for the central municipality rather than picking Koca. Angry, he ran as an independent, placing third. The 2024 campaign was his second attempt, this time against a new MHP nominee.[23] In the strongly pro-AKP province of Erzurum, İYİ nominated Fatma Canan Uçar as its candidate for this nearly impossible-to-win contest. Uçar, a successful local pharmacist, had run in 2019 as the İYİ mayoral candidate in a smaller municipality. In Çanakkale, the party nominated Burak Kunt, the son of a successful local manufacturer. Unopposed by the İYİ in 2019, the CHP had won its largest share of a provincial vote that year in Çanakkale (60.7%); in 2024, the two parties split the vote 39.7% to 36.9%, with the AKP receiving 13,000 few votes and falling to third with 18.3%. Though İYİ lost the race, this was actually its best performance (aside from Nevşehir).[24]

As a splinter of the MHP, the İYİ Party’s identity has always been unclear. Is it more than a vehicle for its leader Meral Akşener? Does the party uphold some ideals of the far-right militia movement that the MHP leadership is betraying through its alliance with the AKP? Voters don’t seem to think so. Nor is İYİ the only party appealing to the nationalist right. The Great Union Party (BBP), founded in the late 1990s by a dissident (now deceased) MHP leader, generally supports the AKP at the national level and in many provinces. Nonetheless, it successfully competed and won the large province of Sivas (the home of its deceased founder).[25] There is also the nativist Victory (Zafer) Party, founded by a disgruntled founder of İYİ. While the İYİ party remains the most popular challenger to the MHP nation-wide, challenging the party in its stronghold provinces like Osmaniye and Aksaray (even out-performing the MHP in provinces like Niğde and Uşak), these performances rarely amount to victories. Meanwhile, in İstanbul, Zafer outperformed İYİ in all-but-four municipalities. None of this makes İYİ’s future look bright.

Even in the İYİ Party's "best" results, it seldom won. Moreover, in the mayoral races that it had previously contested (in 2019), its vote share mostly fell in 2024.The CHP and, Seemingly, Everywhere

The CHP—or, rather, its new CHP leadership—emerged from the elections the unambiguous victors.

In the run up to the elections, many—myself definitely included—had expected that challenges from İYİ and other parties would weaken CHP candidates and lead to the losses. Some worried that strongholds like Eskişehir and İzmir were in play; Eskişehir because the long-serving mayor was retiring, İzmir because the new CHP leadership had replaced the incumbent mayor with a new candidate. There and elsewhere, CHP General Secretary Özgür Özel and İstanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu’s imposition of their allies in safe races had caused a great deal of intraparty discontent. In the İstanbul municipalities of Avcılar and Sarıyer, supporters of the incumbent mayors protested. In the latter, the incumbent resigned from the CHP and launched an independent candidacy. In Ankara, there was also discontent over the choice of Özel’s thirty-one-year old lawyer for mayor of Çankaya district and the star of the popular television drama Behzat Ç for mayor Etimesgut.[26] Yet all these risks were rewarded: Etimesgut was finally won after years of AKP/MHP dominance; Çankaya was won with 65.3% of the vote (admittedly less than the 73.5% in 2019); Sarıyer was won with 51.5% despite the former mayor wining 8% as an independent; and the CHP’s share of the Avcılar increased slightly.

As for the various provincial races, here too success followed success. Of the twenty-one provinces the party won in 2019, it held twenty. The exception was Hatay, where the new CHP leadership stuck with Lütfü Savaş, a long-serving incumbent (and former AKP member) whose decade in office implicated him in the failed municipal management that had aggravated the damage and death-toll of the February 2023 earthquakes. Though keeping him was likely a mistake, it can hardly over-shadow the successes. Of the eighteen provinces that the CHP held, it increased its vote share in six. In five of the twelve where its share dropped, the margin of its victory over the AKP, its nearest competitor, actually increased.

In other words, while the presence of more parties did eat into the CHP’s margins a bit, as one might expect, these loses were offset by the collapse of support for İYİ, and drop in the AKP and MHP’s vote. The largest drop (-9%), for example, occurred in the İzmir metropolitan mayoral race, where İYİ (3.6%), DEM (4.2%), and Zafer (2.5%) all ran candidates. Yet all these parties—the exception being Zafer—actually did worse province-wide than they had in the 2023 parliamentary elections, when İYİ won 11.7% and DEM (at the time called “YSP”) won 7.5%. Meanwhile, the AKP candidate in İzmir received 60,000 fewer votes than his predecessor. These dynamics were repeated in provinces across western Turkey. Ironically, in several provinces, it was the AKP’s coalition allies that undermined it rather than the CHP’s. In Amasya, Kilis, and Kütahya, where the CHP won, the combined vote for the AKP-MHP mayoral candidates was more than for the CHP candidate.

In addition to holding twenty provinces, the CHP won another fifteen provinces including Turkey’s fourth-largest province, the AKP stronghold of Bursa. In fact, of Turkey’s twenty-four provinces with populations over a million, the AKP now controls mayorships in only eight. The CHP controls thirteen, including İstanbul and Ankara which account for a quarter of Turkey’s population. The importance of winning municipal elections is often explained in terms of the opposition gaining resources (“rents”) or the AKP being denied them. But another important effect is the way it familiarizes voters with opposition rule and normalizes it. Reassuring voters that they could govern effectively at the local level was the Islamist movement’s path to power as well.

Finally, in terms of governing, another important CHP success was its ability to win both mayoral races and municipal assemblies. Of its thirty-five major mayoral victories, the CHP won pluralities in twenty-eight assemblies, and none of the seven won by the AKP are in metropolitan municipalities.[27] As a result, CHP mayors, especially in large provinces, will face less resistance when promoting their agendas. This situation will contrast sharply with the past five years. In İstanbul, for example, the AKP’s continuing dominance of the İstanbul assembly both hampered İmamoğlu’s initiatives and his political ambitions—were he to have run for president and won, an AKP-controlled assembly would have appointed his replacement. Moreover, had İmamoğlu been removed as part of one of the cases against him, the AKP would also have regained İstanbul. Now, removing İmamoğlu—though not unthinkable—gains the AKP little and risks creating a political martyr. For the next four years, the AKP may have to be content with controlling Turkey’s national executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government.

The CHP held every province it won in 2019 except for Hatay. In all but three of these provinces, it maintained or gained a plurality in the provincial assembly.

In the fifteen mayoral races that the CHP flipped from AKP/MHP control, it has a plurality in all but five of the provincial assemblies. Also, seven of these provinces were ones in which the CHP did not run in 2019, but differed to the (unsuccessful) İYİ candidate.

[1] Ömer Ürer, “Düzce’nin il oluşunun 15. yılı,” Hürriyet, December 9, 2014.

[2] In 2024, one might note that the CHP received about 27,000 fewer votes than in the parliamentary elections just ten months earlier, but that should probably be understood as a function of local versus national election turnout (the AKP received 37,000 more votes in 2023). Still, what’s notable is that the province contains a larger number of voters who are comfortable voting for the opposition than was manifested in the local elections.

[3] “Renewed” Welfare Party, might be a better translation.

[4] Murat Yetkin, “YRP Cumhur İttifakına katıldı …,” Yetkin Report, March 25, 2023; Murat Yetkin, “Siyaset karıştı: Erdoğan’ın Yeniden Refah ve HüdaPar’la aday pazarlığı,” Yetkin Report, December 14, 2023; Ayşe Sayın, “Erdoğan, Yeniden Refah Partisi’ni …,” BBCTürkçe, December 15, 2023; Ayşe Sayın, “Yerel seçim pazarlıklarında sona doğru …,” BBCTürkçe, February 1, 2024; Ayşe Sayın, “Yeniden Refah Partisi 3 büyük ilde …,” BBCTürkçe, February 2, 2024

[5] The CHP won a majority in the Kırklareli provincial assembly and a plurality in 29 other provinces; of these, there are 9 where the AKP’s percent and the YRP’s percent, in combination, are more than the CHP’s percent. Perhaps more problematically for the CHP: of those 29, there are 12 where the combined AKP/MHP percentage is greater than the CHP’s; and of those 12, there are 9 where the support of İYİ and DEM do not offset this difference. In other words, in these 14 provinces, the CHP’s ability to hold these provinces in future elections may depend on continued competition between the AKP and MHP. (The provinces are Amasya, Artvin, Bartın, Bolu, Kırıkkale, Kırşehir, Kilis, and Yalova.)

[6] The CHP won 26 of İstanbul’s 39 municipal mayoral races. In most of these, CHP candidates defeated their AKP rivals (or, in the case of Silivri, MHP rival) by significant margins. In fact, in 17 of the contests, the CHP won over 50% despite multiple other parties competing. In three races, however, the YRP’s effect is evident. In Beykoz, the CHP won 45.9% against the AKP’s (44.9%) making the YRP’s (2.9%) significant—then again, with such a close race, every vote becomes important, meaning that the small shares won by DEM (0.6%), İYİ (1.1%), and Zafer (1.6%) are also important. In Gaziosmanpasa, where the CHP won by 878 votes, the YRP’s 17,877 would have come in handy for the AKP. Then again, so would the votes of DEM (9.271), Zafer (8,339), Saadet (4,565), İYİ (3,493), BBP (3,3308), or HUDA PAR (973)! In Bayrampasa, the CHP would still have won had every YRP voter swung to the AKP, but such a situation would have narrowed the CHP’s victory to a single percentage point (Ali Dinç and Gonca Deniz Yılmaz, “Gaziosmanpaşa’da sayım bitti: CHP 848 oy farkla kazandı,” Bianet, April 4, 2024).

[7] “Davut Güloğlu’na şiddet uzaklaştırması,” Sabah, October 17, 2014; “‘S… olsun gitsin’ demişti,” Sözcü, November 26, 2020; “YRP’li Güloğlu’ndan Düzcelileri kızdıran gaf,” Düzce Son Haber, November 1, 2023; “‘DÜZCE İLE NE ALAKASI VAR?’“ Düzce Manşet, January 24, 2024; “YRP Düzce Adayı Davut Güloğlu, vatandaşla tartıştı,” Sözcü, March 5, 2024; “Davut Güloğlu kimdir? …,” Cumhuriyet, March 6, 2024

[8] Kahramanmaraş, Düzce, Konya, Elazığ, Kayseri, and Rize.

[9] “Mühür aşiretlerde,” Milliyet, March 20, 1999; “Şanlıurfa’da aşiretler ve büyük aileler yarışacak,” HaberTürk, May 13, 2015; İsmail Kıran, “Aristokrat Kürt Aileler: Gürpınarlar,” The Journal of Mesopotamian Studies 7 no. 2 (2022), 277; “AKP’nin Şanlıurfa’daki gücü …,” Cumhuriyet, September 19, 2022; Ayşe Sayın, “AKP-YRP ittifak görüşmelerinde ilerleme yok …,” BBCTürkçe, January 23, 2024.

[10] Ferit Aslan, “Siverek’te silahlı saldırı ile başlayan görevden almaların kronolojisi,” Medyascope, December 2, 2020; “Siverek’te aşiretlerin güç mücadelesi yerel siyaseti tıkadı, seçimle buna çare aranacak,” Independent Türkçe, December 3, 2020; Abdülaziz Kurt, “AK Parti Şanlıurfa’da Kasım Gülpınar istifaları: ‘Yeniden Refah’a 5 bin üye başvurusu geldi’,” Serbestiyet, January 29, 2024; “Siverek’te toplu istifa: 20 yıllık AKP tabelası indirildi,” Artı Gerçek, February 2, 2024; “Ak Parti’de Kasım Gülpınar İstifalar Adıyaman’a Sıçradı,” KulisTV, February 4, 2024; “Siverek’te iki aşiret yarışıyor: İzoller’e karşı Bucaklar,” Gazete Pencere, March 4, 2024; Ceren Bayar, “Urfa’da üçlü yarış: O ceketi bir kez indirdik, bir daha indiririz,” Gazete Duvar, March 15, 2024; Felat Bozarslan, “Urfa’da ikinci ceket vakası yaşanır mı?” Urfa Star, March 26, 2014.

[11] “Siverek’te seçim sonuçlarına itiraz eden …,” İHA, April 2, 2024; “Mehmet Kasım Gülpınar: Beni torpille meşgul etmeyin,” Gazete Duvar, April 3, 2024. A week later, the provincial election board announced the Siverek election would be rerun; soon after, the national board reversed this ruling (“Siverek’te seçimin yenilenmesi kararı,” Birgün, April 6, 2024; “YSK, Siverek’te seçimin yenilenmesi kararını iptal etti,” BBCTürkçe, April 7, 2024).

[12] “Başbakan Erdoğan, İstanbul Haliç Kongre Merkezi’nde,AK Parti …,” İHA, December 5, 2013; “AK Partili Soysal: Yozgat’ı kıskanıyorlar,” CNNTürk, February 20, 2018; “Yozgat Belediye Başkanı AKP’den istifa etti,” Birgün, February 13, 2019; Mahmut Hamsici, “Yozgat’ta ‘sıra dışı’ seçim …,” BBCTürkçe, March 19, 2019. For a highly critical account of Arslan’s opponent, the incumbent Celal Köse, see Mustafa Babayiğit, “Kamuoyundaki ‘Köse’ algısı AK Parti’ye Yozgat’ı kaybettirmek için mi?” İleri, December 20, 2023.

[13] Mustafa Aydoğar was prosecuted and banned from politics as part of the “February 28” crackdown on Islamist politicians starting in 1997. He took an interest in the AKP during its early years and ran for a spot on the AKP’s candidate list in 2011 but was not included (“‘Kayıp trilyon’ davasında icra başlatıldı,” Hürriyet, September 13, 2007; “28 Şubat’ın siyasi yasaklısı Aydoğar aday adayı’,” Kanal46, March 17, 2011; “AK Parti’nin 80 ilde yaptığı temayül sonuçları,” Sabah, March 22, 2011; “’11 aylık hükümet döneminde başımıza gelmeyen kalmadı’,” Bugün, February 29, 2016; Atilla Şakacı, “Başkan Adayı Muhammed Aydoğar ‘Siz 22 yıldır kimin mirasını yediniz?’” Bugün, March 18, 2024.

[14] “Ahmet Köseoğlu,” Biyografya.com; “YRP’nin Konya Büyükşehir adayı Köseoğlu,” Olay, February 13, 2024.

[15] “YRP Genel Başkanı Erbakan: ‘2028’de denk bütçe ile israfı önleyerek, borçlanmadan milletimizin yüzünü güldüreceğiz’,” İHA, March 2, 2024; “Erbakan: İsrail ile ticaret devam ediyor,” Independent Türkçe, March 12, 2024; “Erbakan: Şartlarımızı yerine getirin İstanbul adayımızı çekelim,” Bianet, March 29, 2024. The Kürecik Radar installation has been controversial from its establishment, criticized by both the CHP and HÜDA PAR. Though the NATO installation is primarily meant to protect US interests against Iran, many people in Turkey worry that it could be used to aid Israel, which is not a NATO member. At the time of the base’s establishment, an (anonymous) US official told reporters that “[D]ata from any U.S. radars and sensors around the world may be fused with other data to maximize the effectiveness of our missile defenses worldwide …Nothing in any of the agreements restricts our ability to defend the state of Israel” (Craig Whitlock, “Turkey agrees to host U.S. radar site,” Washington Post, September 15, 2011; Tom Z. Collina, “Turkey to Host NATO Missile Defense Radar,” Arms Control Today 41 (2011); Burak Bekdil, “Turkey-based NATO radar’s Israel protection in question,” Hürriyet Daily News, July 22, 2014; “Malatya’da ‘Küreciği kapat israili köret’ çağrısı yapıldı,” İlke Haber Ajansı, November 3, 2023.

[16] Aziz Aslan, “HDP’li Zeydan’a 8 yıl hapis cezası,” AA, January 11, 2024; “Abdullah Zeydan kimdir?” Bianet, April 2, 2024; “Van Büyükşehir Belediye Başkanı …,” BBCTürkçe, April 2, 2024; “14 ilde Van eylemleri: 340 kişi gözaltına alındı,” Gazete Duvar, April 4, 2024.

[17] “Mustafa Zeydan Toprağa Verildi,” Beyaz Gazetesi, August 15, 2011; Elem Tuğçe Oktay, “430 yıllık aşiret kavgası: Pinyanişiler ve Ertuşiler,” Hürriyet, June 29, 2014; “Hakkari Milletvekili Abdullah Zeydan Kimdir?” Bianet, November 4, 2016; “AK Parti’nin Yüksekova adayının …,” Independent Türkçe, March 12, 2019; “Rüstem Zeydan kimdir? Rüstem Zeydan AK Parti’den neden istifa etti?” Yeni Akit, August 7, 2019; Ferit Aslan, “CHP Genel Başkanı Kılıçdaroğlu’nun Başdanışmanı …,” Medyascope, November 6, 2021.

[18] “TEOMAN ZEYDAN AK PARTİ’DEN …,” Milliyet, February 21, 2015; “Teoman Zeydan’dan gövde gösterisi,” Hakkari Haber TV, February 27, 2015; [Saygı Öztürk], “Hapisteki HDP’li vekilin ağabeyi AKP’den aday,” Sözcü, March 23, 2019; Behçet Dalmaz and Yaşar Kaplan, “Yine aşiret düğünü! Gelin altınları taşıyamadı, düğüne 15 bin kişi katıldı,” Milliyet, June 5, 2023; “AK Partili Zeydan aday gösterilmedi, Yeniden Refah’ın adayı oldu,” Gazete Duvar, February 20, 2024. Although Teoman Zeydan lost his campaigns in 2015 and 2019, he had the consolation of organizing a large wedding in Ankara in 2022 for his son, attended by then-Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu (“Pinyanişi aşireti kanaat önderi Teoman Zeydan’ın oğlu dünyaevine girdi,” Colemerg Haber, October 9, 2022).

[19] “Kardeşi dağda öldürülen AKP milletvekili,” En Son Haber, December 26, 2007; “Yüksekova’da Zeydan ailesi BDP’ye katıldı,” Evrensel, December 3, 2013. For a particularly through criticism of Abdullah Zeydan, see the article “DYP’nin anonsçusuydu PKK ‘tükürükçüsü’ oldu,” in the pro-AKP paper Sabah, August 2, 2015.

[20] “Meral Akşener, Mansur Yavaş ve Ekrem İmamoğlu’na adaylık çağrısı yaptı,” Evrensel, March 3, 2023. In the following İstanbul municipal mayoral races, İYİ out-performed Zafer: Adalar (+0.2%, i.e. 22 more votes); Arnavutköy (+2.2%, 3,809 votes), Eyüpsultan (+0.4%, 1,009 votes), and Şile (+0.2%, 61 votes).

[21] “Nevşehir Belediyesi’nin 3 eski çalışanı ‘rüşvet ve yolsuzluk’ soruşturmasında tutuklandı,” T24, November 21, 2020; “‘Rüşvet ve yolsuzluk çarkı bütün çıplaklığıyla gün yüzüne çıkarılmalı’,” Fib Haber, December 11, 2020; “Nevşehir Belediye Başkanı Rasim Arı’nın aracına silahlı saldırı düzenlendi,” Evrensel, December 11, 2020; “Nevşehir Belediye Başkanı AK Parti’den istifa etti iddiası …,” Gazete Duvar, January 23, 2021; “Rasim Arı’nın istifası için kim ne söyledi?,” Fib Haber, February 1, 2021; “AKP’den istifa eden Rasim Arı ile ilgili açıklama…,” Sözcü, February 1, 2021; Behçet Alkan, “Nevşehir Belediye Başkanlığına Mehmet Savran seçildi,” AA, February 4, 2021; “Rasim Arı, AKP’den istifasını anlattı: Yanımdaki personeli çöpçü yaptılar ya!” Gercek Gündem, January 21, 2022; “Belediye başkanlığını bırakıp AKP’den de istifa etmişti …,” Cumhuriyet, September 21, 2022; “AKP’den istifa eden eski Nevşehir,” HalkTV, September 22, 2022; AKP’den istifa eden eski Nevşehir Belediye Başkanı Arı, İYİ Parti’ye katıldı,” Birgün, March 29, 2023; “Eski AKP’li Rasim Arı Nevşehir’de farkı açıyor,” Sözcü, March 31, 2024.

[22] “Ordu Büyükşehir Belediye Başkanı istifa etti,” Sözcü, September 18, 2018.

[23] “Belediye Başkanın Katıldığı Düğünde Silahlı Kavga,” Haberler, August 26, 2017; “MHP’li Belediye Başkanı, Oğlunun Arkadaşlarıyla Çatışmaya Girdi: 3 Yaralı,” Haberler, November 14, 2018; Ali Cihangir, “MHP’nin Osmaniye Belediye Başkan Adayı kesinleşti: İbrahim Çenet,” Akdeniz, November 25, 2023; “Alpaslan Koca Rüzgârı Osmaniye’de Çığ Gibi Büyüyor,” Haber Osmaniye, January 4, 2024.

[24] “Mahmut Uçar’lar karıştı!” Doğu Türk, March 26, 2019; Kadir Sabuncuoğlu, “ERZURUM’DA CANAN UÇAR RÜZGARI,” Gazete Pasinler, October 21, 2020; “Eczacı Canan Uçar, İYİ Parti’den aday adaylığını açıkladı,” Alo25, March 20, 2023; “Hakkımızda,” Kunt Plastik.

[25] “Meral Akşener, İYİ Parti Genel Başkanlığı’na aday olmayacak …,” BBCTürkçe, April 8, 2024; “Mustafa Destici/ BBP’nin motive edilmesi için Sivas adaylığı bize bırakılmalı,” Gazete Oksijen, January 11, 2024; “Destici’den yerel seçim açıklaması: İlçelerde Cumhur İttifakı ile işbirliği sürecek,” Birgün, February 9, 2024; “AKP-Yeniden Refah kavgasına Destici de girdi: Adaylarınızı çekin,” VeryansinTV, March 24, 2024. For a discussion of the BBP, see Tanıl Bora and Kemal Can, Devlet ve Kuzgun: 1990’lardan 2000’lere MHP (İletişim Yayınları, 2004), 41-66.

[26] Sözcü, “İsmail Saymaz’dan ‘CHP Eskişehir’i Kaybedebilir’ Çıkışı! Dikkat Çeken Yerel Seçim Analizi,” YouTube, August 3, 2023; “CHP, Etimesgut’ta Erdal Beşikçioğlu’nu aday gösterdi,” Bianet, January 11, 2024; Selim Koru, “Political Analysis #4,” Kulturkampf, January 24, 2024; “CHP’nin Çankaya adayı Hüseyin Can Güner’in hayat hikayesi,” Politik Yol, February 12, 2024; “Özgür Özel Çankaya için avukatını tercih etti! Hüseyin Can Güner kimdir?” Son Mühür, February 12, 2024; “CHP İstanbul il başkanlığı önünde Sarıyer ve Avcılar tepkisi,” Sözcü, February 13, 2024; “CHP’nin İstanbul ilçe adayları açıklandı,” Haber Türk, February 13, 2024; “Sarıyer’de ipler kopacak mı? Aday değişmezse CHP’li mevcut başkan bağımsız adaylığa hazır,” VOA Türkçe, February 19, 2024

[27] In metropolitan municipalities (e.g., provinces with populations over 750,000 like İstanbul, Bursa, Erzurum, etc.), elected mayors are chosen by the whole province. In smaller provinces, mayors of the central municipality do not have the same province-wide authority and are not elected province-wide. At the same time, central municipalities often have the lion’s share of a province’s population. They also tend to have a larger proportion of professional, “state-oriented” voters, which can lead to divergent voting preferences from the other, more rural municipalities in the province. In western provinces, this can produce splits like a CHP central mayor, but an AKP-dominated provincial assembly. In southeast provinces like Bitlis or Şırnak, this leads to an AKP-controlled center, but a DEM-dominated countryside (and accusations that the AKP is registering police and other security forces in the center to skew the vote). In 2024, the CHP won mayoral races in central municipalities in Ardahan, Burdur, Sinop, Giresun, Afyonkarahısar, Adıyaman, and Kütahya while the AKP won the provincial assembly. Of these seven, only in Kütahya did the CHP fail to with the central municipality’s town assembly (“Şırnak, Mardin, Ağrı, Kars, Siirt… Şehir dışından getirilen güvenlik kuvvetlerinin sandıklarda toplu oy kullanmasına tepkiler,” Serbestiyet, March 31, 2024).